MOST OF OREGON'S DRINKING WATER IS SOURCED FROM THE FOREST.

With so many demands on water, keeping supplies safe for drinking is a critical governmental function, one we often take for granted. We simply turn on the tap, and voila!

In Oregon, more than 300 public water providers rely on surface water from rivers, lakes or reservoirs as their main source to supply about 75 percent of Oregonians with safe drinking water.

Nearly half the state is forested, so much of Oregon’s surface water comes from forested watersheds. Some of these are publicly owned and managed mainly as a water resource. Others are privately owned and managed primarily for timber production.

The Oregon Forest Resources Institute (OFRI) provided a grant to the Oregon State University (OSU) Institute of Natural Resources to lead a science-based review of the effects of forest management on drinking water.

At 300+ pages, Trees to Tap is a lengthy report, written by faculty from the OSU College of Forestry who were guided by a statewide steering committee. OFRI distilled that full report into a special report titled Keeping Drinking Water Safe.

Learn more by reading:

Trees to Tap: Findings and Recommendations

Keeping Drinking Water Safe, a special report summarizing the Trees to Tap findings

RAW WATER REQUIRES TREATMENT

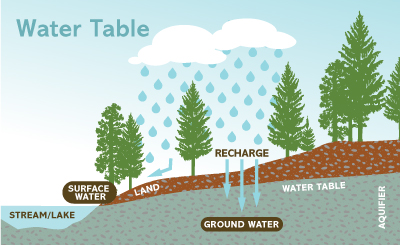

Two types of water make up our water supply: surface water and groundwater. Surface water is subject to both airborne pollutants and ground-based contaminants. As water seeps into the ground, it filters through rocks, roots, soil and organic matter creating the underground water table.

Both surface water and groundwater require treatment before it’s safe to drink. Treatment removes impurities and kills harmful organisms.

Trees to Tap found that forested watersheds, whether managed or unmanaged, produce higher-quality source water than any other type of surface water source. Higher quality source water needs less treatment.

Forest operations can increase sediment into waterways, alter water quantity, and introduce trace levels of chemicals into a stream. The report found that best management practices, laws, regulations, monitoring and scientific research are all needed to protect against these risks and safeguard the quality of source water.

MANY LAWS TO PROTECT WATER QUALITY

Oregon's best management practices program is mandated by the Oregon Forest Practices Act (OFPA). The Legislature passed the OFPA in 1971, and its laws and rules have been modified more than three dozen times since then in response to new scientific information. Regulations that prescribe how to meet the laws are set by the Oregon Board of Forestry and enforced by the state’s Department of Forestry.

ODF Stewardship Foresters administer OFPA rules by working with forest landowners and operators to help them comply with OFPA requirements. Audits through 2017, the most recent data available, indicate high compliance rates – for example, 97 percent overall compliance for 2017.

Numerous federal acts and regulations interlace with Oregon law to protect drinking water quality. These include:

- Clean Water Act (1972)

- Safe Drinking Water Act (1974)

- Oregon water quality standards

- Environmental Protection Agency’s primary and secondary National Drinking Water Regulations

HARVEST, ROADS AND CHEMICAL USE POSE WATER QUALITY RISKS

Safeguarding against forest operation risk requires laws and regulations, constant monitoring and enforcement, management practices based on the best available science and technology, and care taken by skilled loggers and other forest workers.

The potential impact of forest management activities on a community water supply is related to the proportion of the watershed affected, the characteristics of the watershed (slope, geology, rainfall), and operators following best management practices.

HARVEST

Timber harvest reduces canopy coverage and disturbs soils, which can cause erosion and trigger sediment movement until replanted tree seedlings or vegetation reach sufficient size.

While contemporary logging practices are much less impactful than historic ones, any ground disturbance has the potential to generate sediment. The sediment risk is clearly related to the type of harvest operation, and impacted by geology, soil, topography and rainfall patterns.

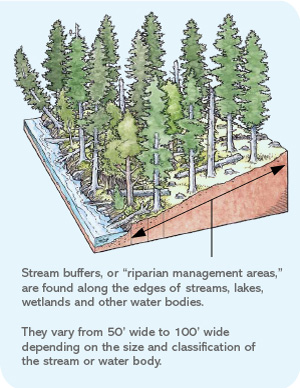

In the short run, timber removal can increase stream flows, which can erode stream banks, saturate soils and scour stream beds that remobilize sediments from past logging and natural disturbances. As stumps decompose, root strength is lost, which can contribute to increased landslide rates. By law and best management practices, forest managers lessen the amount of sediment that gets into water sources by retaining vegetation in buffers on many streams and creating smaller harvest units.

Contemporary logging practices are engineered to lessen the disturbance to the forest floor, and to minimize the possibility of sediment entering streams.

When logging crews are on the ground, their equipment and techniques have a much lower impact than in the past. Instead of dragging logs across the ground or through streams, sky-line cables carry suspended logs uphill to a road on the ridgeline, reducing the contact that a tree has with the forest soil, and transporting the tree uphill, away from a forest stream. Less soil is disturbed, and roads, trucks and other equipment are kept away from streams.

Another crucial tool in source water protection are stream buffers. Oregon law requires leaving buffers of trees and vegetation around streams, rivers, lakes and wetlands that are sources of drinking water or where fish live. Within these buffers, timber harvesting is either limited or restricted. These buffers, left on both sides of a stream, are between 50 and 100 feet wide, depending on the width of the stream.

ROADS

According to Trees to Tap, research consistently indicates that unpaved forest roads are a primary source of sediment entering streams and estuaries in forested watersheds. Any forest road, no matter how carefully constructed, may contribute to soil erosion and potential stream sedimentation.

Over the years, best management practices have evolved for forest road design, placement, construction, maintenance, decommissioning and reclamation. Three examples where significant improvements have been made to reduce the amount of sediment entering streams are:

- actively routing runoff away from streams and toward buffer areas

- improving stream crossings by installing bridges or culverts, to keep road traffic from directly crossing stream channels

- upsizing culvert diameters to increase their flow capacity and reduce the likelihood of failure

Other improvements cited by Trees to Tap include locating roads farther away from streams, avoiding impacts to natural drainage patterns, minimizing total area disturbed by decommissioning and sometimes removing unneeded roads, avoiding steep slopes, avoiding wet areas, limiting the number of stream crossings, using more durable surfacing material and improving routine road maintenance.

CHEMICALS

Forest landowners maintain that insecticides, fertilizers and herbicides are important tools in a forester’s “toolbox” to protect the landowner’s long-term investment. They believe these tools are necessary for successful reforestation and to increase tree growth and yield, allowing forestlands to remain productive and economically competitive.

The use of chemicals in the forest raises public concerns about their effect on plants and animals, adjacent properties and downstream community water supplies. Herbicides are widely used after timber harvest to slow competing growth in clearcuts until planted trees are established. Other pesticides may be used to control for fungi or insects that attack trees. Nitrogen fertilizers may be applied in timber stands to enhance tree growth.

Not all chemicals are used equally. Insecticides are rarely used in Oregon’s forests. Between 2015-2019, researchers found only two instances for applied insecticides on Oregon forests. Fertilizers are also rarely used. If any fertilizer is applied, it is usually nitrogen in the form of urea pellets, an odorless solid that is soluble in water.

Herbicides are the most common chemical used in Oregon’s forests. Forest landowners use herbicides to aid the re-establishment of tree seedlings following timber harvest. These chemicals are a cost-effective means of reducing competing vegetation during the reforestation required by Oregon law.

The total number of treatments on a seedling plantation range from one to four, depending upon the severity of competing vegetation. Herbicides are administered in a controlled application either on the ground or by air. However, chemicals can get into water directly by accident, drift during application, volatilization after spraying or through storm water runoff.

According to studies reviewed by Trees to Tap, traces of herbicides can reach streams via drift during application in the absence of forested buffers, and through leaching or runoff during strong storm events.

Foresters must follow strict rules laid out by a variety of state and federal regulations, as well as the Oregon Forest Practices Act. All of the rules are important and must be followed responsibly for the health and safety of people, aquatic life and drinking water.

Learn more by reading:

Trees to Tap: Findings and Recommendations

Keeping Drinking Water Safe, a special report summarizing the Trees to Tap findings

FOREST FIRE AND WATER QUALITY

Community water system managers are concerned about fire. Forest fires, as well as fire suppression efforts, can affect source water quality. Wildfires can also contribute to concerns for drinking water, including water quantity and erosion; increases in organic matter and sediment; and the addition of chemicals to the watershed if fire suppressants are applied aerially.

Wildfires burn up vegetative cover, including the leaves, needles and branches built up over years. High heat can create hydrophobic soil layers that repel water, reducing the amount that infiltrates the ground. Decreased soil infiltration results in increased overland and stream flow. This can lead to erosion and increased sediment, clogging stream channels and lowering water quality.

Report models showed that rare, large and severe wildfires will continue to occur, especially in the southwest, eastern Cascades and eastern portions of the state. Risk is tied to land ownership. According to model predictions, public lands will be the leading contributor to burned areas in all but the coastal region, where private industrial lands will be the largest contributor.

REPORT SUMMARY

The Oregon State University (OSU) Institute of Natural Resources spent two years leading a science-based review of the effects of forest management on drinking water, yielding a 300+ page report. Their primary findings from that report are available in this one-page summary sheet:

TREES TO TAP VIRTUAL CONFERENCE

On March 11 and 12, 2021, forestry and water professionals, water utilities, regulators, and forest landowners attended a virtual conference hosted by Oregon State University and the Oregon Forest Resources Institute. The conference was a mix of science presentations given by the project scientists and management presentations given by forestry and water professionals, regulators and conservationists. Science presentations gave a high-level summary of the Trees to Tap findings in each topic covered. Management presentations gave an overview followed by practical discussion of how to account for the report's scientific findings in practice.

Each of the sessions and panels were recorded on Zoom for those who couldn't attend.

View the entire playlist of presentations